Would you like to live for, say, 110 years? Does a long life appeal to you? Is it even possible to achieve? Seemingly so. Present-day science is oozing with promises to extend our lives. How would I answer my opening question? That depends. If I were able to survive for well over 100 years feeling as healthy and happy as I am now, I’d shout “You betcha!”

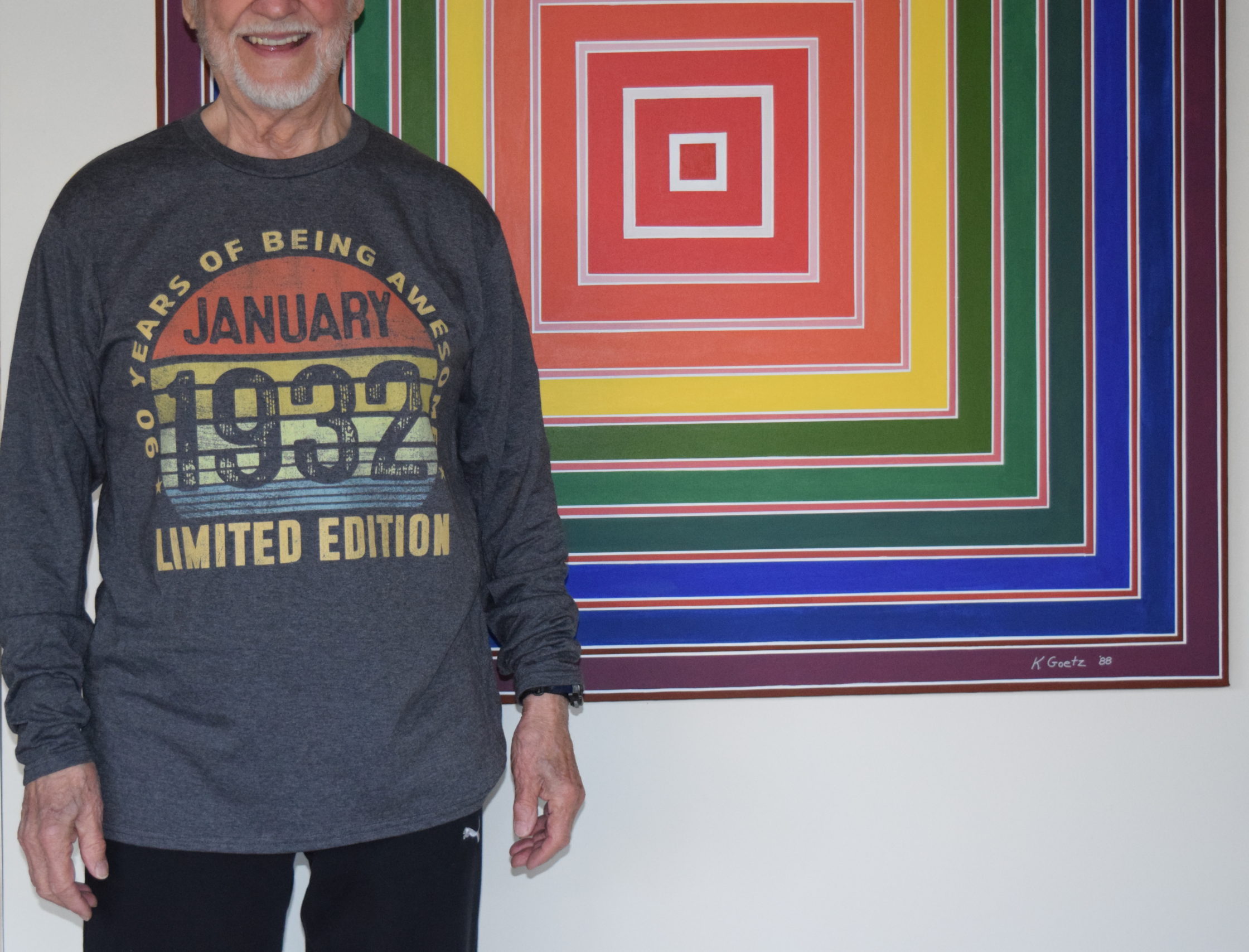

A quick disclaimer: I have not a shred of expertise on aging (other than reaching 90, which merely triggered my curiosity), so an authority I am not. But I’ve nosed around to see what’s going on with those who are devoted to studying our aging processes. A lot is going on! Facts jumped out at me from all directions. Those dedicated scientists, bless their hearts, have learned enough to fill a good scattering of scientific journals. And what they’ve discovered is good news for practically everyone.

For one thing, the thousands of experts who study how we age seem to come together on one important point, namely this. Aging is a decidedly plastic process. It is influenced by a myriad of factors, a good number of which we can influence.

Here’s one collaborating statement that comes from David Sinclair (1), professor of genetics and co-director of a center for aging research at Harvard medical school. What he said shocked me. I didn’t scribble it down as I heard it, so what follows is a paraphrase, but the gist of it was this: 80% of our rate of aging and our health when older is determined by “environmental” (lifestyle?) factors; only 20% is determined by our genome. Wow! Did that snap your eyes open? The evidence backing this statement appears to be solid, and it comes from many sources. What we do through the years is more important than what our genes control. In short, we can live better, and live longer, by adjusting our daily routines.

Controlling our destiny isn’t all new stuff, of course. We’ve known for years that certain habits are bad for us. Smoking is a prime example. The smoke messes up lungs and hearts, among other organs. An article in the New England Journal of Medicine a few years ago ticked off more than a dozen disease processes set into play or aggravated by smoking.

But here we’re talking about good habits. The more recent information concerning our aging, exciting as it is, has been derived largely by untangling rather complex intracellular biochemical pathways, and by digging into intricate genetic mechanisms, but luckily we don’t have to understand all of the complex details to realize what it all means, and to use it to our advantage.

The basic message could not be clearer if it were announced in huge, glowing neon letters. And it is very simple. We have the power (ignoring accidents and bad luck) to slow our “aging,” and to remain healthier longer as we move through the years. This can be accomplished by adjusting our lifestyles (such as walking more, and weight lifting), by dietary alterations (so-called intermittent fasting), by taking certain oral supplements, and even by more experimental and less-available (and less generally accepted) genetic manipulations.

I’ll focus on this theme for a couple of posts. Next time I’ll examine the varying methods of intermittent fasting, an accepted method for prolonging life and preserving health. I’ll even touch lightly on how that approach does the trick to slow down our aging process.

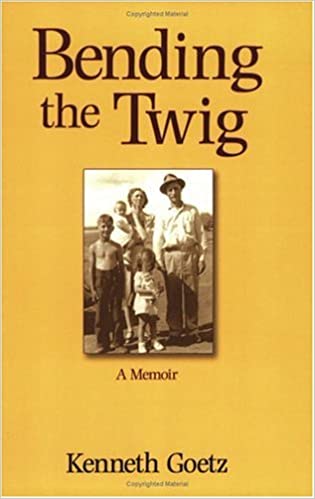

IMPORTANT HOUSEKEEPING NOTE REGARDING THE COLORS OF MEDICINE.

For those of you reading my installments of The Colors of Medicine, I have news. Starting tomorrow (February 1), you will be able to download the complete Kindle version of my novel from Amazon.com at no cost. I’m giving it away free for the first five days in February. I must say it has been fun for me to provide little teasers at the beginning of each installment published here (number 13 was posted yesterday) and I plan to put out one final installment here tomorrow, along with a brief teaser indicating that the story is about to make a rather abrupt transition. I’ll provide more details when I post installment 14.