Resveratrol is a highly touted compound that has multiple health benefits, but it also has characteristics that seem to limit its effectiveness. Here I offer a condensed account of this intriguing chemical.

The story begins almost a century ago, with the discovery in1935, that calorie restriction can increase the lifetime of laboratory rats by up to 33% above their normal life span, a seemingly counterintuitive finding. (see here). Later studies reported even more astonishing results from calorie restriction. Reducing calories in several different species was shown to slow down aging and lengthen their lifetimes by 50 to 300%.

In 1940, a compound was discovered in a Japanese plant and given the name resveratrol. Some two decades after that, resveratrol was found to be present in the roots of a plant that had for many years been used to treat inflammation, cardiovascular diseases, and other common disorders by practitioners in China and Japan.

THE FRENCH PARADOX

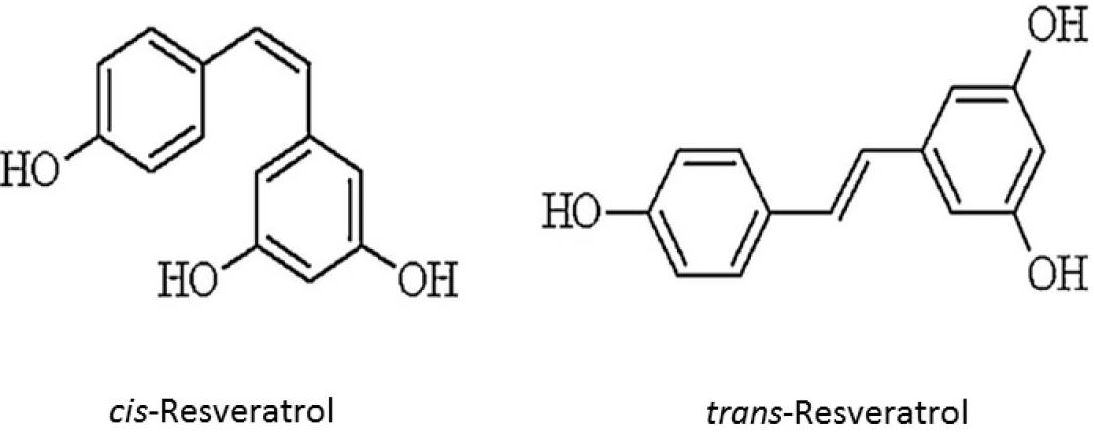

In the 1970s, French epidemiologists noted that French men had a much lower incidence of ischemic heart disease than men from other countries, even though those men ate much more butter, cheese, and pork than did, say, American men. This became known as the French paradox. In other studies, researchers identified resveratrol (3,5,4’‑trihydroxystilbene for you chemists) in blueberries, cranberries, grapes, pomegranates, peanuts, and last but not least, red wine.

Interest in resveratrol exploded after David Sinclair and his colleagues at Harvard University reported that resveratrol prolongs the lives of yeast cells, flies, worms, and mice. In later work, they reported that resveratrol mimics the life-lengthening benefits of calorie restriction. They linked both effects to a group of seven regulatory proteins (sirtuins) found in almost all forms of life. How about that? One didn’t have to starve one’s self to live longer. Just take resveratrol. These startling findings stimulated scientists worldwide to rush into studies of this compound.

THE FRENCH PARADOX REVISITED

Coming back to the so-called French paradox for a moment, the discovery of resveratrol in red wine led some to suggest that the delectable red beverages consumed by the French provided resveratrol which neatly kept them healthy even as they indulged in their rich diets. Skeptics were quick to point out, quite logically, that to consume the amount of resveratrol given in the experiments mentioned above, a person would have to drink hundreds of bottles of wine each day, something beyond even the ablest of Frenchmen.

The intense investigation of resveratrol quickly produced data that were printed in scientific journals. The number of articles soon grew to thousands, most of them reporting positive benefits of resveratrol. To condense this mass of details, certain scientists studied these reports and summarized their contents in scientific reviews. One typical example appeared less than a year ago and provided a broad survey of contemporary ongoing research. The topics covered in that review are extensive. See the list below.

Effect of Resveratrol on Life Extension

Effect of Resveratrol on Age‑Related Diseases

Effect of Resveratrol on Neurodegenerative Diseases

Effect of Resveratrol on Cardiovascular Diseases

Effect of Resveratrol on Sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass and function)

Effect of Resveratrol on Cancers

Effects of Resveratrol on Other Diseases

Mechanisms of Resveratrol on Aging

The Suppression of Oxidative Stress

The Inhibition of Inflammation

The Improvement of Mitochondrial Function

The Regulation of Apoptosis (process of cell death)

The Modulation of Gut Microbiota (Yep, it even seems to have positive effects here too!)

Clinical Trials

If you are interested in learning more about resveratrol, this review would be a good place to start (click here). A DISCLAIMER. This review is written in standard scientific prose. That means it’s full of jargon and is difficult for a layman to follow. NEVERTHELESS, within each of the topics listed above, the authors helpfully include clear declarative sentences that define what resveratrol may do in those specific areas.

When I began this post, I planned to wrap it up about here and mention in my coda that I read of David Sinclair’s work shortly after it was published, adding that I’ve taken resveratrol myself every morning for almost two decades. I’ve even told my family that resveratrol may have helped me reach my Magic 90 milestone (see here). But I have no proof that it actually did.

Science never is straightforward, never cut and dried. Disagreements are a natural part of science. Differing opinions, and differing conclusions from experimental data are common, and they are vital to the process of eventually determining standardized “truths.”

TURBULENCE IN THE RESVERATROL STORY

I mention those scientific truisms because, when I was about to finalize this report, I ran across ripples of turbulence in the resveratrol story. Because I strive for accuracy in everything I put on this blog, I felt compelled to expand this story. Please bear with me as I tiptoe around this turbulence without taking sides.

To be clear, I’ve seen few contentions that resveratrol has no positive effects, or that it may be dangerous to take (except for a lone report that it may have an adverse effect on the kidneys). Rather, one point of dispute deals mainly with what resveratrol actually does within our cells, how it alter ours cellular metabolism. In brief, a number of competent scientists have not been able to confirm the Harvard group’s claim that resveratrol activates sirtuins. (This is a big story in the resveratrol field, but it’s beyond the scope of what we’re covering here.)

Others critics have taken exception to the technical quality of certain experiments, arguing that the protocols used were insufficient to justify the conclusions drawn from the experimental data presented. Beyond that, resveratrol is not well absorbed into the body (trans-resveratrol is absorbed better than cis-resveratrol), and its availability to cells may be poor. Again, I’m condensing quite a bit here.

So, has resveratrol been over hyped? Does it promote health and longevity? Is it worth taking? As I hope I’ve made clear, scientists disagree on this. As for me, I plan to keep taking my morning capsule (trans-resveratrol, with yogurt because it’s better absorbed with fat ), not because I’m fully convinced of its benefits, but because I’m chugging along well at 90, I’ve taken it for two decades, and, admittedly, habits are hard to break at my age.

If you are thinking of giving resveratrol a try, it would be wise to check with your doctor to see what she thinks about that.

HOUSEKEEPING ADDENDUM

I have two major projects looming over me, each obligatory and each requiring long hours of boring personal effort. So it’s necessary that I take a little break. I plan to return here in early April to report on a couple of other compounds that have excited investigators of the aging process (many of theose investigators take one or both of the putative aging-extending drugs I’ll describe).

In the meantime, please consider familiarizing yourself with some of my earlier posts, which are longing for fresh eyes. One of my most popular essays describes my incredibly accurate internal clock (see here), a rare gift I discovered when in high school. I’ve also described classic medical experiments, such as the first cardiac catheterization (that was in 1929, and by the way, the heart the doctor catheterized was his own [see here]). I followed that up with three more essays on cardiac catheterization (see here, here, and here). Elsewhere I’ve told of the doctor who voluntarily took 2 ½ times the lethal dose of curare, the South American arrow poison, and lived to tell about his experience (see here). I’ve also described my travels to Berlin and Russia, each with political overtones (see here, here, here, and here), a trip to Rome and beyond (see here), and youthful travels to Portugal and Spain (see here, here, here, and here). And there are many more. And all are free! Have I given myself away? Can you tell that I love readers?